Exodus

Population expulsions marked the conflicts on the territory of the former Yugoslavia. According to international law, ethnic cleansing is considered a crime against humanity. Its purpose is to create “pure” ethnic regions or to minimize the number of members of another ethnic group. During the conflict in Croatia in 1991, up to 200,000 Croats were expelled from the territory occupied by Serbian forces and the JNA, comprising one-third of the Republic of Croatia’s land area. Between 5,000 and 7,500 Serbs were expelled after Operation “Flesh” (Bljesak) in May 1995 when the Croatian Army seized parts of western Slavonia previously held by the Republic of Srpska Krajina. Following the military-police operation “Storm” (Oluja) that began in early August 1995, more than 200,000 Serbs fled or were expelled from Croatia.

During the war, Bosnia and Herzegovina experienced the most extensive ethnic cleansing. It is estimated that more than 2 million of its citizens were forced to flee their homes—1 million were internally displaced and 1,2 million fled abroad—which was Europe’s largest post-World War II exodus.

During the NATO bombing in 1999, 750,000 Albanians were displaced from Kosovo. After the signing of the Kumanovo Agreement and the withdrawal of the Yugoslav Army, approximately 100,000 Serbs fled the area, almost half of the Serb population in Kosovo.

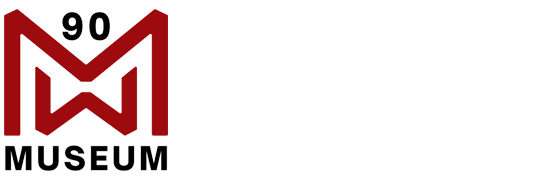

The photograph by Imre Sabo shows Serb refugees fleeing Croatia during Operation “Storm” (August 1995).

Sources: The Hague International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia; Human Rights Watch.

Camps

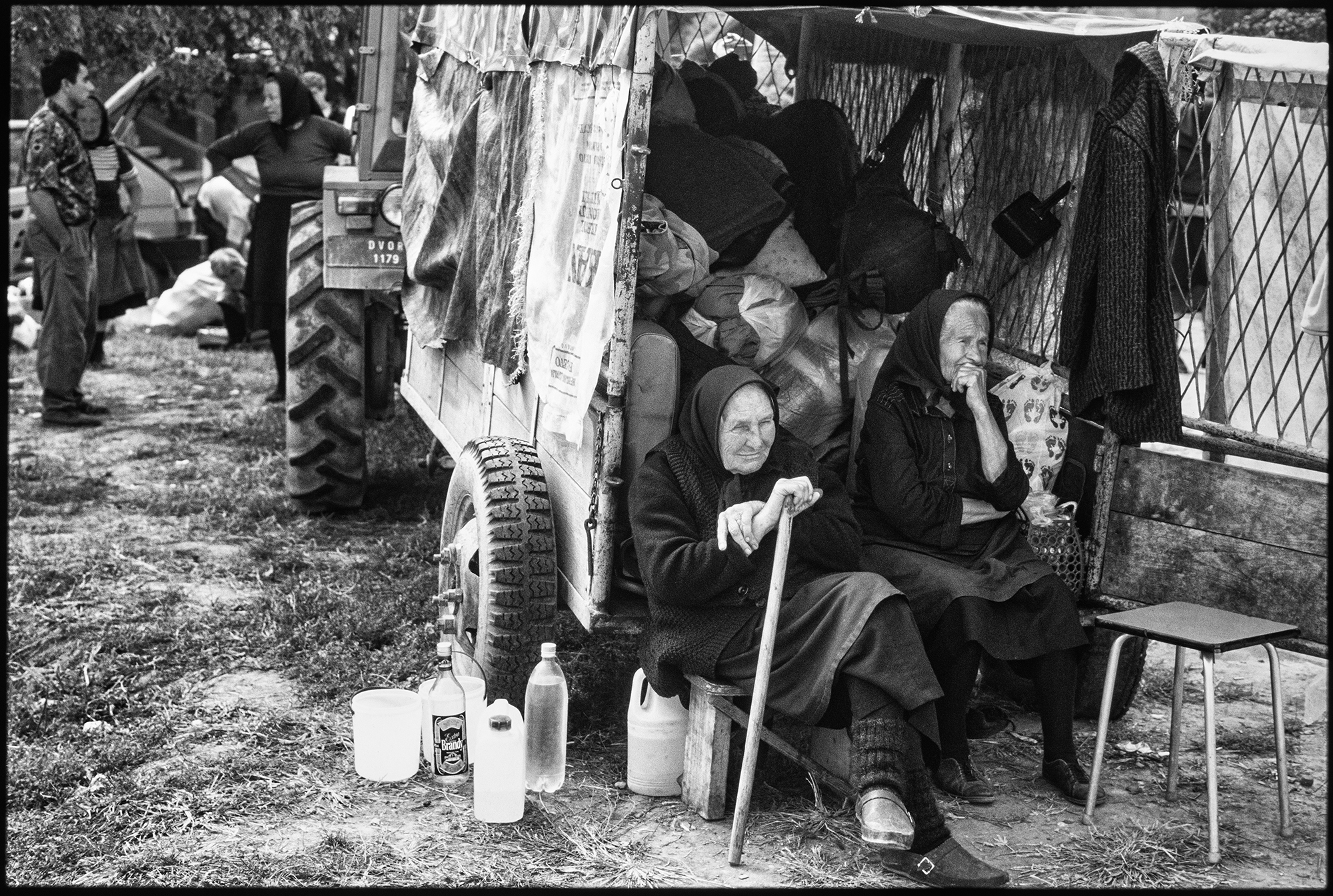

Amidst the conflicts in the 1990s, many camps were erected, wherein tens of thousands of individuals, including both civilians and prisoners of war, were detained. It has been established that, apart from inhumane treatment, in these camps acts of torture, rape, and murder. The revelation of these camps and the initial televised footages of emaciated individuals confined behind the barbed wire shocked Europe and the global public. The Serb forces organized some of the most sizable detention camps, namely Omarska, Keraterm, and Trnopolje in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as Vukovar and Pakrac in Croatia. In the Bosniak-Croat conflict, Croat authorities established detention facilities in Herzegovina, including Dretelj and Heliodrom, while Bosniak military units held Serb prisoners in the Čelebići camp. These camps were a component of a broader strategy of ethnic cleansing and extermination.

Rape

Women were victims of sexual violence, including rape, sexual abuse, coerced matrimony, and forced pregnancy during the wars in the region of the former Yugoslavia. The exact number of women who were subjected to rape remains unknown due to under-documentation of these crimes, and the reluctance of many victims to report such acts of violence due to societal stigmatization. Nevertheless, according to estimates, at least 25,000 women were raped.

Rape was a method of ethnic cleansing used by all parties involved in the hostilities. Serb forces perpetrated systematic mass rapes in eastern Bosnia and near Prijedor in 1992. These acts involved the detention of women in camps and resulted in the rape of thousands of Bosniak-Muslim but also Croat women. The enduring impact of sexual violence on victims encompasses both physical and psychological consequences, with forced pregnancies resulting in the birth of numerous children.

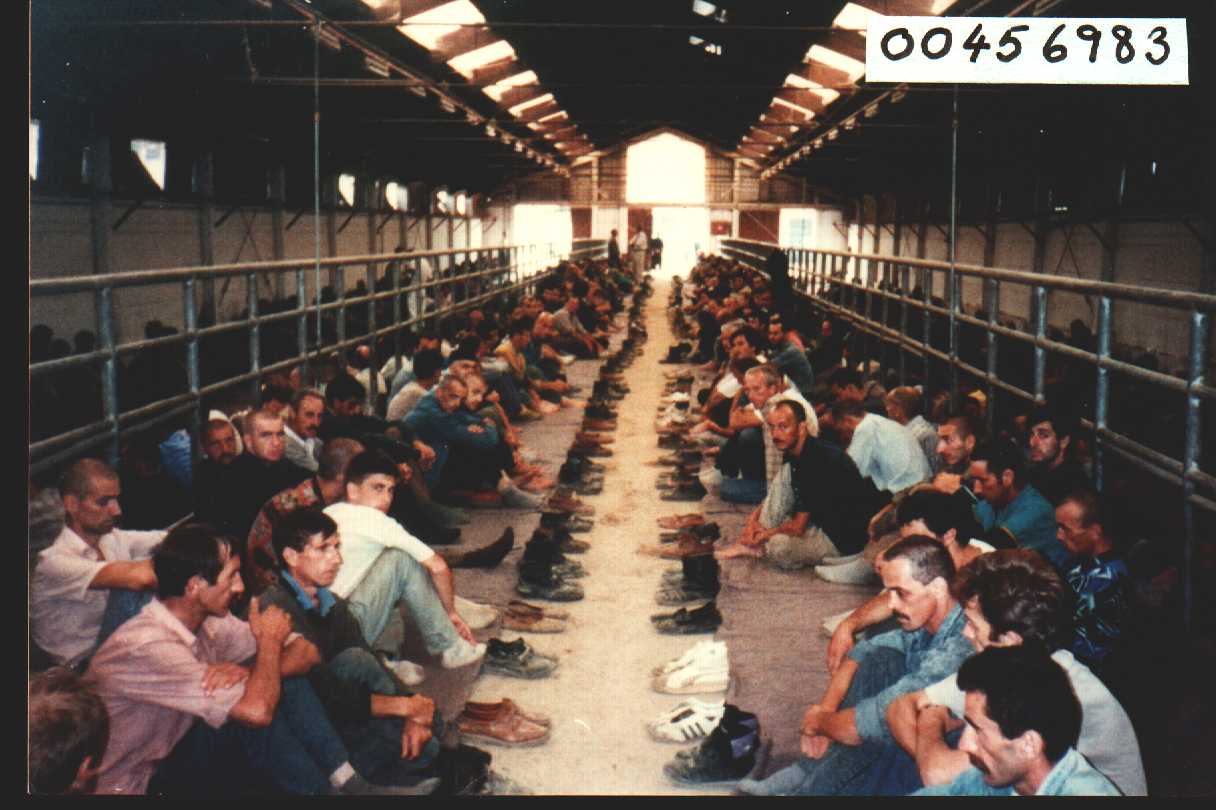

The image shows the Karaman house in Miljevina, near Foča, which served as a site of confinement and sexual violence against numerous Bosniak women in 1992. The victims were held captive in the house for an extended period. For those crimes, Dragoljub Kunarac, Radomir Kovač, and Zoran Vuković were found guilty and sentenced to 28 years, 20 years, and 12 years in prison, respectively, by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY).

Source: International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in The Hague.

Killings

The precise death toll (number of casualties) of conflicts in former Yugoslavia remains uncertain. However, it is estimated that roughly 130,000 individuals perished.

Bosnia and Herzegovina had the highest number of casualties. According to estimates, approximately 100,000 individuals lost their lives during the conflict, with Bosniak losses comprising 30,500 military personnel and 31,500 civilians, Serb losses comprising 21,000 military personnel and 4,000 civilians, and Croat losses comprising 6,000 military personnel and 2,500 civilians.

The war in Croatia is estimated to have resulted in approximately 20,000 fatalities.

The conflict in Kosovo resulted in approximately 10,000 fatalities, with most of the casualties being individuals of Albanian descent.

The image shows a refrigerator car that was retrieved from the Danube River. It contained the remains of Albanian civilians, including female, children, and elderly, who were killed during the Kosovo conflict in 1999. The filmmaker Ognjen Glavonić produced a documentary entitled “Depth 2” and a feature film called “The Load,” on the atrocities committed against Albanian civilians and the subsequent concealment of these crimes by the Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs.

Sources: Research and Documentation Center in Sarajevo; The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in The Hague.

Expulsion

The plan to establish ethnically pure states was not solely carried out through physical violence but also through legal and administrative means. Following the dissolution of Yugoslavia, the newly formed independent states implemented citizenship laws that prioritized individuals belonging to their ethnic majority or their co-ethnics in nearby regions. This resulted in varying degrees of discrimination against individuals of different ethnic backgrounds or those originating from other republics. Furthermore, a significant number of individuals encountered administrative barriers and harassment. The acquisition of citizenship in the newly independent states was tied to employment, access to healthcare, eligibility for property ownership, and the enjoyment of political rights. Numbers of full citizens were turned overnight into foreigners, residents, or stateless individuals. As a result, numerous people departed from their residences, relocated to other post-Yugoslav states where they felt more secure, or migrated to foreign countries as emigrants.

The photo shows a canceled Yugoslav passport issued in Celje, Slovenia. In February 1992, the Ministry of Internal Affairs of newly independent Slovenia erased about 25,000 persons from the citizens’ register who did not have a proof of Slovenian citizenship at the time. Most individuals were migrants from other Yugoslav republics, alongside a portion of native-born Slovenes. Their documents were confiscated and subsequently invalidated. Numerous deaths due to the loss of healthcare were recorded, as well as several instances of suicide, and many left Slovenia. The case of the “erased” [izbrisani] was revealed in the early 2000s, and it harmed the image of Slovenian “transition” and secession from Yugoslavia, that was perceived as a model. The European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg condemned Slovenia for this case in 2012.

Obliteration

The obliteration of the cultural heritage of different ethnic and religious groups, commonly called “cultural cleansing,” was a crucial component of ethnic cleansing. This was done to eliminate all indications of multiculturalism and co-existence. Mass demolition of religious structures was carried out to attain ethnic and religious uniformity. As an illustration, approximately 200 mosques were destroyed by Serbian forces in Kosovo, whereas Kosovo-Albanian forces were responsible for the destruction of roughly 150 Orthodox churches and monasteries.

Several buildings with significant cultural and historical value as representations of ethnic communities or cities were intentionally destroyed during the conflict. For instance, the Croatian side deliberately targeted the Old Bridge in Mostar, while the JNA, with the aid of Serbian and Montenegrin paramilitaries and reservists, shelled the old town in Dubrovnik. Additionally, the Serb forces were responsible for destroying the Ferhadija Mosque in Banja Luka and the National and University Library in Sarajevo.

The photos show the Orthodox Church in Mostar before and after its destruction in 1992.

Siege

A prominent warfare and political strategy involved the besiegement, destruction, and blockade of urban areas, accompanied by extensive shelling and sniper assaults targeting civilians. The sieges of Vukovar, Dubrovnik, Sarajevo, and Mostar are among the most notable. The siege of Vukovar, conducted by the JNA and affiliated Serbian paramilitary forces, persisted for nearly three months, from August 25 to November 18, 1991. The siege of Dubrovnik, carried out by the JNA, Serbian paramilitaries from BiH, and Montenegrin reservists, lasted eight months, from October 1, 1991, to May 31, 1992. The Army of Republika Srpska laid siege to Sarajevo for almost four years, from April 5, 1992, to February 29, 1996. Lastly, the Croatian Defense Council (HVO) besieged the eastern part of Mostar for a year, from May 9, 1993, to the spring of 1994.

The photograph by Milomir Kovačević Strašni shows the water tower in Vukovar after the end of the siege. The water tower became a symbol of the Homeland War in Croatia as well as the resistance and suffering of Vukovar.

Destruction

During the hostilities in Yugoslavia, material devastation was enormous, including a wide range of damage to infrastructure, industry, and property. Cities under siege suffered the most significant material destruction, as buildings, residences, bridges, and other infrastructure were strategically destroyed. Moreover, during the fighting and aerial bombing, numerous factories, estates, highways, and other essential infrastructure were damaged. In the aftermath of the war, most of the remaining industrial structures were ruined during the privatization process.

The photograph by Emil Vas shows the bridge situated in the Grdelica Gorge that was subjected to an aerial attack by NATO on the April 12, 1999. At the time of the attack, a train with about 50 passengers was crossing the bridge. A total of nine corpses and four parts of human bodies were found. The exact number of fatalities has not been determined.